Three Polish mathematicians, led by Marian Rejewski, were the first to decipher the German Enigma machine in 1932. Their work laid the foundation for the future work by British code breakers at Bletchley Park during World War II. Many people will recognize the name Alan Turing, a brilliant British mathematician credited with solving the Enigma. Yet why don’t we hear about the critical Polish contribution?

My theory is because they were Polish. The historical British lack of public respect for Poles ran deep. As but one example, recognition and inclusion on Armistice Day of the more than 200,000 Polish veterans who fought with the British armed forces did not occur for sixty years, in 2005. (See earlier blog post on this topic.) Secondly, the 2014 film The Imitation Game omitted all references to the Polish contributions.

Thankfully, more and more people are giving long overdue credit where credit is due.

What was the German Enigma device?

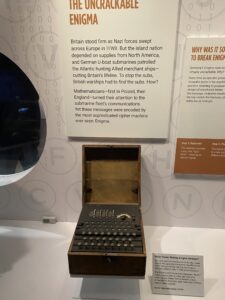

German engineer Arthur Scherbius designed the machine at the end of the First World War. The Enigma was a commercial cypher machine that would later be adapted for military use by all branches of the German armed forces. Resembling an oversized typewriter, the purpose of the Enigma machine was to encrypt messages by scrambling them into supposedly indecipherable strings of random letters. In 1924, the German Navy began broadcasting a new type of encrypted message that baffled the Poles.

The Poles first encountered the machine in 1928. By the end of December 1932, Marian Rejewski of the Polish Cipher Bureau, deciphered messages sent with the Enigma. Fellow mathematicians Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski worked closely with Rajewski in the Polish Cipher Bureau.

The team of cryptologists took a different approach than other code breakers in France and Britain. They focused on the mathematics of the code, rather than linguistics. Poles also had a closer grasp of the German language and instinct for their habits. In 1936, and again in 1937 and 1938, the Germans added more rotors and complexity to the machine. Still, Rajewski and his team were able to crack most of the code.

The Poles were reluctant to share their accomplishments with their allies. In July 1939, the Poles knew war with Germany was imminent. Why? Because with their copy of the Enigma they decoded ninety-five percent of German radio transmissions. They knew the battle plans and planned German invasion of Poland. They met with their British and French counterparts and turned over a reconstructed Enigma machine. They included instructions on how to break the code longhand, a manual for the machine, and transcripts of intercepted German messages. The British and French were stunned at what the Poles had accomplished. The Polish Cipher Bureau relocated to France. Historians estimate the contributions saved at least two years’ work in breaking the Enigma code.

Again, due to lack of respect for the Poles, all three mathematicians were excluded from further contributions on the Enigma. German codebreaking became strictly a British and American project. Very few people ever learned of the Poles’ contributions, especially as a classified operation.

The 2014 film The Imitation Game was about Alan Turing, not the story of the Enigma machine.

I looked forward to watching The Imitation Game when it came out in 2014. It grossed more than $233 million worldwide. That’s a lot of viewers exposed to Alan Turing’s name, and the view that he was the only problem solver to decode the device. It was a great movie, and who can argue with casting the fabulous Benedict Cumberbatch as the conflicted Alan Turing. Yet, once again, the huge contribution of the Poles, who handed the machine and codes to the British and French, garnered nary a mention.

More than 9,000 men and women eventually worked at the secret Bletchley Park, working on decoding messages. They deserve substantial credit, especially the preponderance of women involved. Due to the sheer volume of German messages to decode, the work consumed hundreds of people. There are many resources and books out there portraying the valuable work the British codebreakers performed. One hallmark of success–the Germans never knew their ‘unbreakable’ codes had been broken.

My wish is for the whole story to be told, not just one version. A key part was the bombe machine, a device first developed to crack the codes. Alan Turing did not design the machine by himself. He improved on the Polish design. Fellow British mathematician Gordon Welchman played a key role in helping Turing build the machine that decoded the Enigma. Again, no mention of or credit to Welchman either.

In 1997, Welchman published his own story in the book The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes.

Broad recognition finally arrives.

In 2002, Bletchley Park dedicated a memorial sculpture to the Polish mathematicians. It stated, in English and Polish, that Rejewski, Różycki and Zygalski were the first to crack the Enigma code.

On November 19, 2014, the families and descendants of the Polish mathematicians, Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki, and Henryk Zygalski were invited to a special ceremony at Bletchley Park. The Polish Embassy UK produced an excellent five-minute video highlighting the Poles. It has both Polish and English subtitles.

In 2018, Dermot Turing, Alan Turing’s nephew, published X, Y and Z: The Real Story of How Enigma Was Broken. The book focuses on the Polish code-breakers. He notes the codebreakers continued to work for Her Majesty’s Secret Service during the Cold War, watching the Russians. I discovered the book while writing this blog, so I can’t comment as to its quality. But given that Turing’s nephew is the author, I will add it to my list of books to read. Alan Turing’s nephew has published multiple books about his famous uncle and the decoding of the Enigma machine.

This Spring I visited the International Spy Museum in Washington D.C. This history and spy geek loved it. I was thrilled to see the story of mathematician Marian Rejewski in a prominent display under World War II codes. Even better, the museum features the four-rotor Enigma machine in the top of their collection highlights on its website.

For further information on the Engima Machine and the Polish cryptologists, here are a few credible sources I located.

BBC News, July 14, 2011. “Bletchley Park remembers Polish code breakers.” Click here.

Polish Embassy UK, November 19, 2014. Video of ceremony. Click here.

TimeGhost History Channel, May 26, 2020. Video “The Battle to crack Enigma – The real story of “The Imitation Game” – WW2 special. Click here to watch.

The Front Channel, July 21, 2021. Video “How these Heroic Polish Codebreakers set the Foundations for the Allies to Crack Enigma.” Click here to watch.

Website for author Durmot Turing. Click here.

Together, we can keep history alive.

In friendship and gratitude,